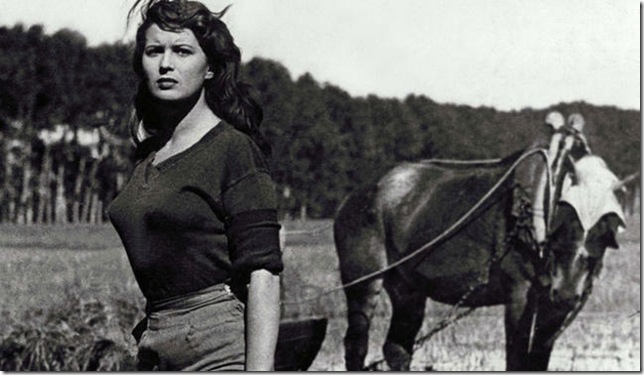

Silvia Magnano in Bitter Rice. (1949)

Bitter Rice: A tragedy on tenterhooks, Giuseppe De Santis’ Bitter Rice (Criterion, $22.99 Blu-ray, $17.99 DVD) is a slippery fusion of docu-naturalism and noir expressionism. And with its first proper Region 1 release now widely available, it should earn its rightful place in the feminist film pantheon.

Released in 1949, Bitter Rice is set among the rice paddies in the Po Valley of Italy. It’s the start of rice-planting season, where women ranging from factory workers to peasants will kneel down in the marshes for the next 40 days, completing tasks described by a local journalist in the opening frames as distinctly women’s work: designed for “the same hands that thread a needle and cradle an infant.”

It’s a perfect milieu for lovers-on-the-run — Francesca (Doris Dowling) and Walter (Vittorio Gassman) — to blend in after they’ve stolen a $5 million diamond necklace from the Grand Hotel, an item that looks plenty appetizing to Silvana (Silvana Mangano), a rice planter and a gum-smacking, tabloid-devouring fount of irrepressible sexuality. Throw in an earnest, soon-to-be-discharged soldier (Raf Vallone) who’s fallen under Silvana’s femme fatale spell and you’ve got the makings of not a love triangle so much as a lust quadrangle: one that is divided not between “good” and “bad” characters, but between the redeemed and the rotten, the wholesome and the corrupt.

This is neither the Italian neorealism of De Sica nor Rossellini; with the possible exception of Luchino Visconti’s debut Ossessione, I can’t think of another picture from the movement that so fluidly shuffles between social realism and pulp melodrama. It contains references to PTSD, illegal immigration and forced abortion — and in a haunting series of shots late in the film, a rape is implied. Yet De Santis still finds room for a defiant musical number and a pair of exciting dance sequences that helped establish Mangano as an international sexpot.

The art of Bitter Rice is high, low and everywhere in between. Just when you think you’ve grasped this singular film, it changes tone, texture and plot, coalescing in much hothouse delirium and a masterly climax in a slaughterhouse. Criterion’s digital restoration ensures that every documentary detail and chiaroscuro flourish look equally vivid, and bonus features include a 2008 doc about De Santis directed by his screenwriter colleague, Carlo Lizzani.

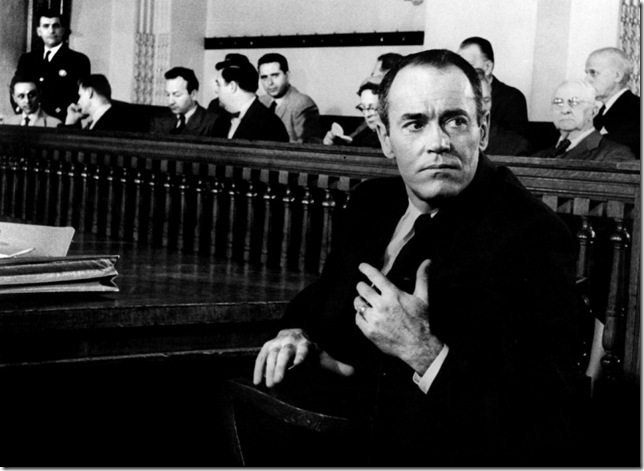

Henry Fonda in The Wrong Man. (1956)

The Wrong Man: The downside of being an everyman is that you look like every man — and can easily be confused with the countless doppelgangers shuffling across New York City in identical coats and hats, not all of whom have the best intentions. In The Wrong Man, newly issued on Blu-ray (Warner, $17.99), Henry Fonda’s Emmanuel Balestrero is a squeaky-clean middle-class striver, dutiful father to two precocious boys, and loving husband to homemaker Rose (Vera Miles).

He performs bass fiddle for the One Percent at a ritzy nightclub, a job that earns enough income only to keep the lights on and the kitchen stocked. When Rose informs her husband that she needs an expensive dental extraction, Manny attempts to take out a loan against her life insurance policy — at which point he is fingered for a robbery he didn’t commit by the waifish tellers, the first domino in an escalating tragedy that would be Kafkaesque if it weren’t so grounded in gritty reality.

Famously, The Wrong Man is the first Hitchcock film based on a true story. For the first time, he combined the frill-less, austere rigor of reportage to his obsessively precise mise-en-scènes, resulting in a minor-key variation of the wrong-man archetype explored more floridly in North by Northwest and The 39 Steps, among others. Aside from the two instances of formal derring-do you’ll notice immediately, Hitchcock films an increasingly enraging miscarriage of justice with an eye for documentary detail — the scarred walls and slack electrical wires of the police precinct, the spartan accommodations of the cell where he spends an excruciating night.

The director sees bars everywhere — at the insurance office, over a window at the police station — and makes sure to place Fonda’s face behind or in front of them, suggesting the fate he doesn’t deserve. One of Bernard Herrmann’s most underrated scores translates the character’s grim descent through penal protocol through a procession of ominous, jazzy nocturnes (this is the film that prompted Martin Scorsese to enlist Herrmann for Taxi Driver).

The Wrong Man may be Hitchcock’s most spiritual, and socially conscious, film. Manny Balestrero, who clutches rosary beads for much of the picture, emerges as an urban Job, taking each test and indignity in stride, while Maxwell Anderson’s screenplay critiques the inaccuracy of eyewitness testimony decades before such questioning became de rigueur. Virtually free of Hitch’s trademark suspense, this matter-of-fact nightmare is a modernist masterpiece, the Hitchcock drama that looks most like the art-house films it inspired.

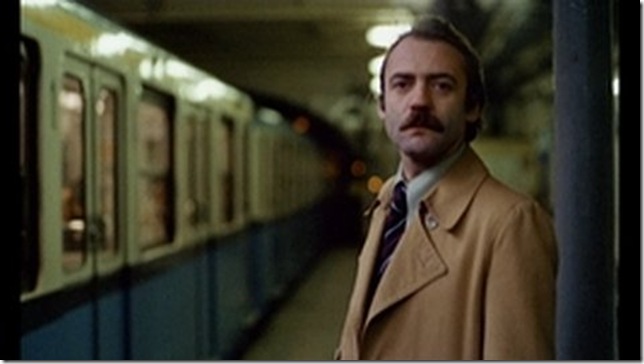

Bruno Ganz in The American Friend. (1977)

The American Friend: As the storied literary con man Tom Ripley, Dennis Hopper exudes a soft menace in Wim Wenders’ multicultural neo-noir (Criterion, $22.49 Blu-ray, $19.09 DVD), adapted loosely and auteuristically from Patricia Highsmith’s Ripley Game. Ripley is in Hamburg, where he runs an art-forgery scam with a one-eyed painter (played, with presumably little acting, by the one-eyed Nicholas Ray). The scheme puts him in the same circle as Jonathan Zimmermann (Bruno Ganz), a Swiss picture framer and art restorer who suspects the con — and who happens to be suffering from a fatal blood disorder. When this information leaks its way to Ripley and his accomplice, the French gangster Raoul Minot (Gerard Blain), they manage to blackmail Zimmermann into murdering some rivals in return for all-expense paid “specialized” treatment overseas.

More languid than pulpy, The American Friend moves like an art-house dreamfilm, offering a spellbinding meditation on American film history and culture, preoccupations that have persisted throughout Wenders’ curious, globetrotting oeuvre. Two of the classical American cinema’s finest progenitors — Ray and Samuel Fuller — are cast here in rough-and-tumble roles, and the Tom Ripley of Hopper and Wenders’ imagination dresses like a cowboy in exile, on loan from Paramount in the ’40s. American bands and American brands fill the soundtrack and the mise-en-scène, respectively; the prismatic plot, too, plays like Dashiell Hammett on a slower speed.

Wenders had just finished his Road Movie Trilogy when he embarked on this offbeat adaptation, and you could argue that The American Friend is the fourth in a quadralogy. Most of the action takes place on various forms of transit — in funky-looking cars, on the Metro, on old-fashioned Hitchcockian trains, on airplanes and in airports. There’s a death on an escalator, and another slumped-over body at the end of a moving walkway, an omen never quite explained. It’s all painted, by cinematographer Robby Mueller, in shades of red, blue and green that Crayola has never conjured. The American Friend won’t appeal to everyone, but if you find its groove, it’s a strangely mesmerizing achievement: Modern Germany reinvented with the ghosts of movies past.

Gary Oldman (left) and Tim Roth in Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead. (1990)

Rosencrantz and Guildenstern Are Dead: Minor cult figures from Hamlet share two hours of spotlights in this absurdist comedy directed by Tom Stoppard (Image, $19.14 Blu-ray, $10.69 DVD), based on his breakthrough play of the same name. We first encounter Rosencrantz and Guildenstern (Tim Roth and Gary Oldman, or possibly Gary Oldman and Tim Roth, we’re never quite sure), riding on horseback through the mountains, destination unknown.

Guildenstern comes upon a gold coin and proceeds to flip it 156 times, landing on “heads” in every instance. This triggers a discussion of (im)probabilities and proto-quantum mechanics, which the travelers discuss while Guildenstern munches on an anachronistic double cheeseburger. Then, without warning, they are thrust into the company of Richard Dreyfuss’ Player, who leads a ragtag troupe of itinerant tragedians that will eventually produce Hamlet’s famed play-within-a-play.

And so it goes, with the existential comedians and this stentorian theatrical director galumphing through Shakespeare’s flawless universe and running roughshod across it. Impossible transitions, visual and temporal illusions, witty wordplay and Brechtian self-reflexivity form the core of Stoppard’s revisionist vision, in which puppet shows and slapstick comedy rub elbows with existential musings on mortality and morality. The Bard’s original work is in there somewhere too — at least the Cliff’s Notes.

Roth and Oldman make for a master class in deadpan comic timing, and even if the film occasionally sputters on its axles — suffering, as it were, from the same aimlessness as its protagonists — it’s such an inventively postmodern experiment that moments of tedium don’t last long. This was Stoppard’s only film as a director, which is too bad; his command of the medium is better than many playwright-turned-filmmakers.