Close-Up (Criterion)

Release date: June 22

Standard list price: $36.49

This two-disc Criterion reissue of one of the greatest – if not the greatest – films of the 1990s replaces the out-of-print edition from Facets, and hopefully a new crop of young cinephiles will discover it. Iranian master Abbas Kiarostami wrote and directed the film after reading a short magazine article about a man named Hossein Sabzian, who was arrested for impersonating well-known Iranian filmmaker Mohsen Makhmalbaf. Sabzian convinced a family he was Makhmalbaf, and this being the pre-Google age of the late ’80s, they believed him. They even letting him live in their home for a few days after the promise that “Makhmalbaf” would shoot a movie in their house, with themselves as the cast.

Kiarostami soon found out Sabzian was no run-of-the-mill con man looking for money to steal; he was an obsessed moviegoer who felt a deep sense of himself in Makhmalbaf’s (and Kiarostami’s) films and relished the illusory power of living in the auteur’s shoes – and in his psyche. Close-Up is Kiarostami’s exploration/re-creation of the events leading up to, and including, Sabzian’s fraud trial, with the principal players all reprising, and reliving, their real-life encounters.

Part documentary, part dramatic reenactment, there has never been anything quite like Close-Up before or since its release, and that’s partly what makes it so special. It examines the manipulation of reality and the nature of the documentary film, and how people change and adapt in the presence of a camera. Sabzian is a character more worthy of our pity than our scorn, and Kiarostami treats the disturbed man with empathy and even understanding. After all, Sabzian’s rationale – cinephilia as justification for fraud – is almost romantic at a time of all-digital movie theaters, disappearing arthouses and dwindling art-film distribution.

The bonus features make this release an essential addition to your collection, even if you already own the Facets DVD. Criterion has a charming little habit of tossing compelling, unreleased early features from prominent directors on bonus discs with little fanfare – see Jim Jarmusch’s Permanent Vacation and Richard Linklater’s It’s Impossible to Learn to Plow From Reading Books, on the Stranger Than Paradise and Slacker DVDs, respectively, and here they’ve thrown us a real gem: The Traveler, Kiarostami’s first true feature and a movie for which Sabzian, in his trial, confesses his love.

The black-and-white, verité-style film anticipates Kiarostami’s breakthrough feature Where Is the Friend’s Home? by focusing its narrative on a rural child’s quest, this time to earn enough tomans to steal away to a major soccer match in Tehran (you can also draw a direct line from The Traveler all the way to the similarly themed Offside, a masterpiece directed by Jafar Panahi; the best films about children in the world continue to be produced in Iran). Gently criticizing economic disparity and the unfairness of the world, The Traveler is an unabashedly inspiring movie in which the character’s journey is far more important than his destination.

Close-Up’s second disc provides more than 90 fascinating minutes of reflection and analysis from Kiarostami, Sabzian and Sabzian’s friends and neighbors: It’s a sort of documentary post-mortem of the world after Close-Up, divided into three featurettes. In the documentary Close-Up Long Shot, made six year’s after Kiarostami’s film, Sabzian remains a pitiful soul, but he’s filled with poetic insights. He candidly admits that “I let my love for cinema destroy my life,” just before the director’s camera lingers on a copy of the Koran that rests atop an instructional book about making movies on Super 8.

Sure enough, some time later, as Kiarostami recounts in a newly recorded interview featurette, Sabzian’s life would end at 52, and it was the cinema that killed him: He collapsed into a coma at a subway station on the way to meet film students who were to film him before he was to meet Kiarostami for a retrospective screening of Close-Up. With this grim endnote in mind, I’m left wondering if there has ever been a film that so eloquently expresses the immense power and influence of the very medium. Close-Up belongs at the Met and the Smithsonian as much as it does your Netflix queue.

Bluebeard (Strand)

Release date: June 22

SLP: $21.49

Admirers of Catherine Breillat know the French director as one of the cinema’s foremost purveyors of frank deconstructions of female sexuality and gender representation. That said, her latest film – an arch, emotionless rendering of Charles Perrault’s bloody fairy tale Bluebeard – may seem an unusual choice for the director. More straightforward than not, her terse adaptation lacks key Breillatian themes, namely the uninhibited sexuality that dominated even her repressive period piece, The Last Mistress. Bluebeard cuts between a poker-faced retelling of the 1697-set Bluebeard fable, about a young girl betrothed to an ogreish aristocrat, and a more modern depiction of two adorable French girls who discover the Perrault text in their mothers’ attic. The contemporary story has an appealing sense of comic spontaneity, even when its frequent interruptions desensitize us to the 17th-century drama and remind us we’re watching a movie –undoubtedly a deliberate distancing device on Breillat’s part. Bluebeard is, like much of Breillat’s oeuvre, more engaging as intellectual theory than entertainment. It’s an interesting work, but because it fails to provoke or subvert the gruesome folk tale in any way – feminist or otherwise – I couldn’t help but see it as a missed opportunity for the normally confrontational auteur.

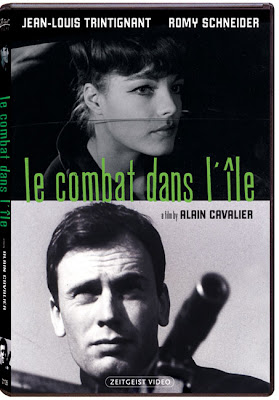

Le combat dans l’ile (Zeitgeist Films)

Release date: June 22

SLP: $22.49

An esoteric soundtrack and luminous black-and-white photography mask a rather conventional story in French director Alain Cavalier’s stylish debut feature, Le combat dans l’ile. When abusive militiaman Clement (Jean-Louis Trintignant, The Conformist) is framed for an assassination attempt by the leader of his extremist political organization, he flees to Buenos Aires to kill the man. His wife Anne (Romy Schneider, Cesar & Rosalie), hiding in Paris, kindles a new romance with Clement’s old friend and modest printer Paul (Henri Sierre), who brings out the radiant stage actress Anne had long repressed. When Clement finally returns, he naturally wants his girl back, leading to a bloody duel between the two men. Released in 1962 at the height of the French New Wave, Cavalier’s film found itself lost to history amid the Godards, Truffauts, Malles and the other darlings of hip Francophilia. Its narrative and obligatory political ambience may come off as a bit rote today, but like many of those masters’ films, its formalism feels every bit as (post)modern as the day it was released.

Green Zone (Universal)

Release date: June 22

SLP: $17.49

There’s an inherent problem with Paul Greengrass’ Green Zone, and it’s not the shaky, adrenalized, faux-realistic camerawork that’s become the filmmaker’s signature (though viewers who succumb to frequent motion sickness might want to avoid this one, ditto to the director’s Bourne movies). The problem lies more in the screenplay, about a courageous whistleblower (Matt Damon) from the U.S. army’s team of WMD hunters who works to expose lies and corruption surrounding the Bush administration’s justification for war in the early days of the occupation of Iraq. Most of the chief characters have real-life counterparts who have been written about extensively in books such as Bob Woodward’s State of Denial and Rajiv Chandrasekaran’s Imperial Life in the Emerald City, the latter of which inspired Brian Helgeland’s script: Damon’s character is modeled after chief warrant officer Richard Gonzalez, Greg Kinnear’s inept Pentagon bureaucrat is clearly based on Paul Bremer, Amy Ryan’s muckraking journalist is almost certainly Judith Miller, etc. Because the story is based on such recent – and widespread – public knowledge, the amount of suspense, twists and dramatic tension is almost nonexistent; forget any chance of new revelations about the whole sordid affair. Still, Greengrass tries his darndest to turn Helgeland’s moral lecture on the war crimes of the previous administration into a straightforward action movie, and at this he mostly succeeds, despite scattered bouts of hand-cam incomprehensibility.