There may be no better example of a film’s prologue forecasting its themes than the exhilarating aperitif that opens La Dolce Vita.

A helicopter, its heavy cargo suspended from wires, delivers a statue of Christ to its final destination in St. Peter’s Square. Trailed by a second copter of tabloid reporters and photographers, the spectacle traverses an ancient Roman aqueduct, flying over ruins, then cranes and high-rises and beautiful women sunbathing on the roof of a resort. Momentarily distracted by the swim-suited bodies, the reporters, led by the insatiable skirt-chaser Marcello (Marcello Mastroianni), attempt to gather the onlookers’ phone numbers, an impossible task over the whir of the propellers. Christ, evidently, can wait.

The thrilling and transcendent juxtapositions of La Dolce Vita are encapsulated, wordlessly, within these few surreal minutes: History and modernity, the sacred and the profane, materialism and asceticism. Despite introducing the film, the sequence is so iconic that it feels like a centerpiece, not a prologue. It’s a testament to Fellini’s own lust for life — not for the transient upper-crust bacchanalias sought by Marcello but for a daring and boundless exploration of cinema’s possibilities — that every scene in this hulking critique of the decline and fall of Western civilization feels like a centerpiece.

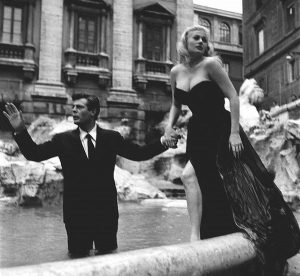

While seeing the movie for the third time on Paramount’s gorgeous new Blu-ray release ($13.99), restored in 4K by the Cineteca di Bologna and the Film Foundation, I had forgotten too many of its ravishing visuals, its insights, its paradoxes. I had forgotten how consistently funny it is, and the tarnished grace with which Fellini transitions from rowdy humor to its sobering flipside. Like the moment Sylvia Rank (Anita Ekberg), a buxom Swedish-American actress alighting in Rome, frolics in the Trevi Fountain, anointing Marcello just as dawn’s harsh light disrupts the revelry, not to mention the flow of water. Suddenly they appear as well-dressed vagrants, sopping wet amid a trickle of prying eyes. Soon, Sylvia will be assaulted by her boyfriend.

The moment marks one of many instances in La Dolce Vita in which the unsustainable fantasy life of the Roman leisure class screeches headlong into reality, taking occasional casualties along with it. In his introduction to the film recorded for the disc’s release, Martin Scorsese comments that Fellini channeled the “anxiety of the nuclear age.” Indeed, Marcello, in his libidinous but unsatisfying weeklong odyssey, embodies the sense of a culture facing down the barrel of its own existence, grasping at the last filaments of pleasure until the walls come tumbling down. Time and again, his high-life adventures are the prelude toward a crushing comedown. We see Camelot, then its end, only to be revived by defibrillators and vanquished once again. Wash, rinse, repeat.

While not the first film to skewer gutter journalism, La Dolce Vita condemns the tabloid press as handmaidens to the apocalypse and the symbols of its rankest instincts. Marcello and his colleagues, like the photographer Paparazzo (sound familiar?), are more than happy to influence a story, shaping reality for a more salacious image. Even miracles — especially miracles — like a purported vision of the Madonna by local children, are cause for the media’s craven exploitations.

Though not a coming-of-age story — it’s more of an end-of-an-age story — the episodic structure of La Dolce Vita has influenced generations of filmmakers, its presence deeply felt on such 2022 Oscar hopefuls as The Hand of God and Licorice Pizza. Fellini allows us to spend only a serialized week with Marcello, but with a cinematic canvas as enormous and sweeping as Rome itself, we see enough. We see, essentially, the fall of Pompeii.

And like the dead but open-eyed leviathan dredged from the sea by fishermen following the latest of Marcello’s debauched all-nighters, we cannot turn away from this sordid twilight. To paraphrase Marcello, we, like the bloated beast, “insist on looking.”