Kino Lorber recently retrieved three titles from the distributor’s seemingly bottomless well of obscure noirs from the genre’s golden age for yet another impactful box set. The Dark Side of Cinema XXI ($33.22 Blu-ray) features three titles that largely dance around the traditional expectations of noir, mixing its shadowy atmosphere with timely espionage drama and hothouse sexual politics.

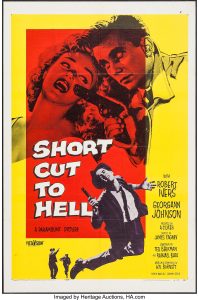

In fact, the most straightforward noir in the set is also the weakest. Short Cut to Hell (1957) will always have an asterisk in the film history books, because it’s the lone directorial effort from James Cagney. Based on a Graham Greene novel (which also inspired 1941’s This Gun For Fire), this generically titled thriller stars the James Dean-ish Robert Ivers as nihilistic contract killer Kyle Niles, who completes a job for a foppish client (Jacques Aubochon) only to find himself double-crossed by his employers. While fleeing to Los Angeles by train, with the police in pursuit, Kyle finds a convenient cover in Glory Hamilton (Georgann Johnson), a wholesome cabaret singer who happens to be dating a police sergeant, and whom Kyle tethers to himself for 39 steps and beyond.

The ingredients are all there for a crackerjack piece of entertainment, as Short Cut to Hell barrels from L.A. penthouse to nightclub to underground hideaway to an industrialist’s palatial estate. But the writing, from Ted Berkman and Raphael Blau, is just not as clever or witty as the best noir touchstones, and Cagney’s direction is serviceable but undistinguished. Its most enduring trope is the hitman-as-antihero archetype, which would be approached with more nuance in the decades to come.

The most notable inclusion in this volume is certainly Fritz Lang’s WWII spy film Cloak and Dagger (1946), shot during the peak of the director’s American noir heyday, and released between Scarlet Street and Secret Beyond the Door. There are few faces in the classical Hollywood canon more trustworthy than Gary Cooper’s, who plays Alvah Jesper, a nuclear physicist at a Midwestern college who is secretly working on the Manhattan Project. Recruited by the Office of Strategic Services to thwart Germany’s nuclear weapons program from the inside, he becomes our surrogate into the dangerous corners of the Axis war effort.

Unlike many titles in Kino’s noir collections, Cloak and Dagger is a genuine “A” picture, a glossy and patriotic tribute to the unsung work of American spy agencies and the underground resistance movements in Europe. But it must have held some personal connection for Lang, a German expatriate who relished any opportunity to defeat the Nazis on celluloid (Lang’s original, more impactful ending to the film, rejected by its producer, would have revealed the remnants of an underground factory and the bodies of dead concentration camp workers).

Lang’s mastery of chiaroscuro lighting and sustained suspense are on full display, and he achieves a convincing ambiance of perpetual paranoia, where evil lurks around every corner, every word and gesture must be carefully chosen, and chance encounters can spell certain doom. A sufficient amount of twists and choreographed set pieces — there’s a menacing example of grisly hand-to-hand combat in an apartment lobby, the sounds of folk music from an Italian piazza wafting in from outside — carry this sophisticated spycraft through to its Casablanca-like climax.

But saving the best for last, 1955’s Shack Out on 101 is an unheralded diamond in the very rough. Reflecting its blunt, ramshackle title, co-writer/director Edward Dein’s movie revels in lecherous gazes, dark conspiracies and fryer grease.

Keenan Wynn plays George, long-suffering owner of the titular “restaurant” where the entire film takes place, but Lee Marvin’s magnetism carries the day. He plays Mr. Gregory, AKA “Slob,” a short-order cook and a lean, mean Brandoesque bruiser whom we first see forcibly kissing and groping the diner’s waitress, Kotty (Terry Moore). Slob is the recipient of some of screenwriters Edward and Mildred Dein’s most memorable lines: “Even when you’re clean, you look dirty.” He’s also noted for having “an eight-cylinder body and a two-cylinder mind.” But Slob is no mere dim-witted hash slinger at a greasy spoon: He’s secretly trafficking in nuclear secrets, presumably working for the Soviets in a plot that has led to a pattern of suspicious “suicides” of prominent scientists, and that may involve Kotty’s professor boyfriend, Sam (Frank Lovejoy).

Shack Out on 101 trades in some but not all of film noir’s audiovisual argot, from a swinging overhead light casting pendular shafts on characters’ fisticuffs to the wailing trumpets that often signal the arrival of the blonde bombshell Kotty. But there’s more skeevy weirdness on display than noir convention, right down to a murder weapon straight out of Melville, and to the chilling atmosphere of male predation that suffuses every moment.

As the only woman with a speaking part (I have to concede that this one gets an F on the Bechdel Test), Moore’s character is leered at or molested by just about everyone who enters the diner. She’s as much a piece of meat as the corroded hamburgers that come off the grill, and Dein shows us how sexual violence can easily beget other forms of it. A stealth feminist film may not be the recipe the producers sought to create with Shack Out on 101, but it’s the secret ingredient of its subversive staying power.