By Hap Erstein

“Change, but no progress.”

That is how the tireless advocate for federal and state anti-hate crime legislation Judy Shepard describes the past 10 years since her gay son Matthew was brutally murdered in Laramie, Wyoming.

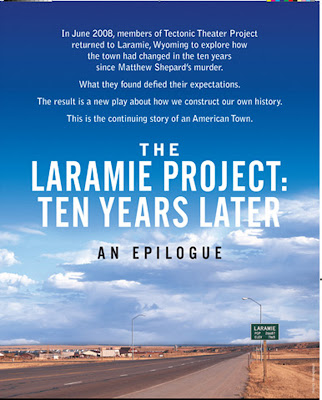

That killing and its aftermath were captured by Moises Kaufman and his Tectonic Theater Project in the much-produced 2001 docudrama The Laramie Project. Monday night, on the 11th anniversary of Shepard’s death, theater companies across the United States and around the world participated in simultaneous readings of an epilogue/sequel, The Laramie Project: Ten Years Later.

In all, an estimated 146 companies participated from all 50 states and such countries as Canada, Great Britain, Spain and Hong Kong. Although the original play had its South Florida premiere at the Caldwell Theatre, it was Manalapan’s Florida Stage that was tapped to represent the region in this shared premiere.

While reviews of the play were specifically discouraged, and the script does have an unfinished, unshaped feel to it, the evening as an event had a sense of global community and an unsubtle call to action that argued efforts to eradicate hate crimes are still in their infancy.

As with the first play, the members of the Tectonic troupe trekked to Laramie to interview the locals, injecting themselves into the play with reenactments of transcripts of their conversations. Ten years later, they found signs of growth in the town — the Walmart had been transformed into a Super Walmart — but the townsfolk were largely in denial about the Shepard case.

Trying hard to shake off the label of Hate Crime Central, many of those interviewed preferred to think of the college student’s death as a “robbery gone bad” perpetrated by a couple of druggies, with the victim’s sexual orientation all but incidental. Such a view was clearly refuted by the testimony at the trials of Russell Henderson and Aaron McKinney, the two young men accused of and convicted of Shepard’s murder, but the residents of Laramie as represented here do not seem to let facts get in the way of their opinions.

The first act of Ten Years Later is a series of “moments,” snapshots of the encounters, with a flatness to the dramatic arc that seems intent on mimicking the Laramie terrain.

The payoff comes after intermission, with face-to-face prison interviews with Henderson and McKinney, the latter a remorseless figure who simply sees himself as an abject criminal. Only briefly present in the first play because of a lack of access to them at the time, their views a decade after the fact are one of the play’s most compelling pieces of the Laramie puzzle.

Also involving is a tangential battle in the Wyoming legislature over a defense-of-marriage bill, with Wyoming emerging as one of the few states in the autumn of 2008 to defeat efforts to define marriage as exclusively between a man and a woman.

The 18-member Florida Stage cast included producing director Louis Tyrrell, managing director Nancy Barnett and public relations director Michael Gepner. Among the other cast members were such frequently seen area actors as Dan Leonard, Bruce Linser, Lourelene Snedeker and Karen Stephens.

The only no-show of the evening was Tony Award winner Glenn Close, who hosted the reading at Lincoln Center’s Alice Tully Hall and was to have introduced the reading via streaming Webcast. But despite all cyber-efforts, Close was unable to be conjured up by Florida Stage’s technical staff. So much for the blend of new technology and good old-fashioned live performance.

Florida Stage drew a packed house for the event at $30 a seat, with the proceeds going to The Shepard Foundation and to Compass, Palm Beach County’s gay and lesbian services organization.