By Tara Mitton Catao

It is a tall order for a dance company to perform, side by side on a single program, the works of an iconic artist such as Martha Graham (who is responsible for shaping and redirecting a whole art form) together with new works by contemporary choreographers who may or may not have been influenced by Martha Graham’s genius.

But that is exactly what the Martha Graham Dance Company is doing.

It was unfortunate that there was a program change in their only performance at at the Kravis Center on Tuesday. The resulting rearranging of the program order made the journey in the first half of the program — from a 1906 excerpt of a Ruth St. Denis work to an intense new piece from 2013 by Nacho Duato — a bumpy trip.

It was intended that the first half of the program would have contained the earlier works and that the newer and more substantial works would have been in the second half of the program. Nevertheless, despite the bumpy ride, the dancers rose to the challenge of not only honoring and breathing fresh life into works that are epochal and need to be seen, but also diving headfirst into new and creative endeavors.

The first part of the program, Prelude and Revolt, was narrated by Janet Eilber, who has been artistic director of the Martha Graham Dance Company since 2005. She led us through the rich history of Martha Graham and explained how Graham’s vision of movement was sculpted not only by her personality but also by the times in which she lived and worked. Eilber, who was a principal dancer under Graham’s tutelage, highlighted the historical importance of the section as we viewed archival slides, films and and excerpts of various works.

But it was the roles that Graham created for herself in her constant quest for self-expression that vibrated in Tuesday evening’s performance at the Kravis Center. The sheer power of her gestures and the use of the torso to convey human emotion are deeply authentic and still resonate in this more contemporary world.

In Errand, which Eilber described as a new arrangement of Errand into the Maze (1947), Blakeley White-McGuire was fiercely powerful in her role as Ariadne as she entered the maze and encountered the Minotaur danced confidently by Abdiel Jacobsen. Though the memorable sculptural sets and costumes from the 1947 version were missing, this pared-down version accentuated the exceptional depth of White-McGuire’s artistry and her incredible mastery of the Graham technique as she dealt with and conquered fear.

White-McGuire also danced the solo, Serenata Morisca, which was choreographed in 1916 by Ted Shawn. In the role as a slave girl, she was more subtly captivating as she alluringly danced with a red rose in her hair, bells on her feet and a weighted skirt that swirled around her. White-McGuire is the quintessential Graham dancer and a true embodiment of Graham’s famous observation: “Great dancers are not great because of their technique; they are great because of their passion.”

The women continued to shine with a strong performance from Carrie Ellmore-Talltisch in Lamentation, one of Graham’s most well-known solos, which is performed on a bench wearing a long tube of dark cloth.

In 2007, continuing with the tradition of artistic collaboration for which Graham was known, a project was conceived to commemorate 9/11. Three choreographers were shown a film of Graham dancing Lamentation and were asked to create “a spontaneous choreographic reaction” to it. The result was Lamentation Variations, which is now a part of the company’s repertory.

Ellmore-Talltisch and Ying Xin danced the female duet by Aszure Barton, which was beautiful in its simplicity with its attention to tiny gestures that flickered throughout their bodies.

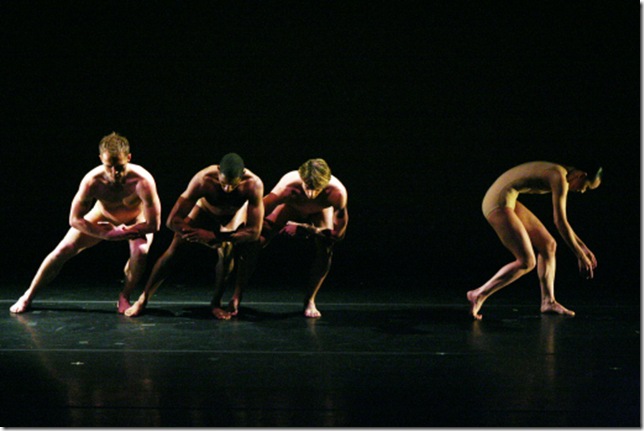

Rust, a work commissioned for the Graham Company by the Carolina Performing Arts and choreographed by Nacho Duato (who once studied with Graham), is a somber dance for five men that depicted the grim subject of human torture. The sacred music, by Estonian composer Arvo Pärt, together with the moving lights designed by Brad Fields (which at times resembled interrogation lights and at other times diffused sunlight filtering down from a cathedral dome) gave a sense of changing perspectives of different locales, almost like a video game.

But the amplification of the music was piercingly overloud and the stage so dark that it was difficult to make out the movement of the five men as they lifted and caught each other and dissolved into piles of body parts that were reminiscent of the terrible images of concentration camp gas chamber victims.

There is a feeling of substance and purpose in what the Graham Company (which is the oldest dance company in the United States) is trying to achieve as it as it transitions into its 88th season. They are clearly committed to preserving and sharing the dances of a master choreographer but they are also committed to collaborating with new choreographers and artistic growth for their dancers and, very importantly, they are strongly committed to education and instilling in young people a passion for self-discovery and creativity.

After Tuesday’s performance, and as a former student of the Graham technique and as a continuing professional in this art form, I reflected on my training and the lasting influence and perspective it has given me in my field. I can recognize what an influence Martha Graham has been and I value what her artistry has imparted to me.