The Fifth String Quartet of American composer Kenneth Fuchs, which had its world premiere Sunday afternoon at the Colony Hotel in Delray Beach, is an effective piece of dramatic music first and foremost, with a big-boned grandeur that shares sonic space with an intense and hearfelt elegy.

Fuchs, a professor of composition at the University of Connecticut, grew up in Fort Lauderdale and wrote the work at the behest of the Delray String Quartet, which gave the premiere and will play it again Friday night and Sunday afternoon. The composer said in remarks to an appreciative house last Sunday that the quartet, subtitled American, is a reflection on his country in the post 9-11 era.

Formally, the quartet is laid out in four movements, the outer two essentially in A major and the middle two in the neighborhood of D minor, all with traditional attributes such as sonata-allegro form, a scherzo and a double fugue. Its language is tonal, occasionally minimalist, and highly accessible, with a blue-skies feeling to much of it that derives from Fuchs’ extensive use of counterpoint and individual lines.

All of the material in the quartet is derived from the opening theme, a long-breathed, slow, Coplandesque canon that starts with the first violin and continues down to the cello. It’s one of those themes that promises a lot, and its derivations later in the quartet were clear to discern, again because the solo-line texture Fuchs sets up at the beginning accustoms the ear to single them out. The Delrays played this opening, which is marked for a very slow tempo, much too quickly to make the proper transitional effect from its stateliness to the exuberance of the rest of the movement. Nonetheless, it was pretty and evocative, and was played with an admirable level of commitment.

The first movement sets a difficult challenge for the foursome, dominated as it is by a bustling variation of the theme that requires an athletic bow and precise intonation at a high rate of speed. The effect is one of great optimism and energy, and exciting to hear. Each member attacked the assignment with gusto, building up a big cathedral of sound before the music darkened and set the stage for the scherzo.

The second movement, an agitated Shostakovich-style march, turns into a movement of almost constant motion, with long passages of pizzicati and fast-stepping motifs played in unison by all four members. Early on, the viola plays a dark-hued melody derived from the theme over a nervous pizzicato in the cello that ends up extending for pages; violist Richard Fleischman and cellist Claudio Jaffé played this beautifully, giving it a strong sense of dark energy. This is a powerful, propulsive movement, and it got a fine performance from the quartet.

The third, marked Elegia, again hints at Shostakovich by starting (after a minor-key version of the opening) with a sad-carousel waltz theme in the second violin’s upper registers that gets taken up by the whole ensemble and ultimately turns into an aggressive, sardonic version of itself before what may be the elegy itself appears toward the end of the movement. This section also received a fine performance, though the very first bars could have been a good bit slower, more mysterious, to make a clearer contrast with the second movement.

And the music of the movement is cut from much of the same cloth as the second, which also made the two middle movements sound almost like one continuous piece. Perhaps if the second movement were played more drily, the differences would stand out better. Also, the elegy at the end, which received an intensely emotional performance, could perhaps be a little longer, especially as the movement itself is designed to be the heart of the work.

The finale returns to the open-prairie feeling of the first, with a fugue subject as close to a fiddle breakdown as it could get, and when all four instruments took their turn at it, the effect was joyful and confident. The last movement doesn’t introduce much distinctive new material, but it serves as a welcome return to the cheerfulness of the first pages. This also provided the quartet’s members with a major workout, and they pulled it off admirably.

The Colony audience applauded the piece vociferously, and there is no doubt about its ability to engage listeners. Kenneth Fuchs has written a fine piece of music in this quartet, one that could conceivably fill the new-music inclinations of American string quartet concerts in an absorbing way. It also seems to me that the last two movements could be rescored for string orchestra (call it Elegy and Fugue) and make a most attractive contemporary piece for chamber orchestras.

The Delrays will record this quartet later this month for an all-Fuchs disc on Naxos, and one looks forward to hearing the piece again, as well as to celebrating the composer’s achievement and the progress made by this homegrown string foursome.

That said, the rest of the concert demonstrated where the Delray quartet has its most persistent weak spot, and that is in the core Germanic repertory of the late 18th and early 19th centuries. This is a group much more successful with late Romanticism than the Classical period, and the first half of Sunday’s concert provided another example.

The first piece on the program was the Quartet No. 52 (in E-flat, Op. 64, No. 6) of Haydn, one of the composer’s late masterworks. Although the relatively rich opening was full and warm, the rest of the movement had a lot of rough playing. First violinist Mei Mei Luo’s triplets sounded labored rather than charming, and the quartet did nothing with the four-note back-and-forth extended passage except let the notes just sort of lie there. Further, the return of the opening material in a different, remote key needed much more color to make its impact.

The second movement was stronger, especially in the Sturm und Drang second section, but the third-movement Minuet sounded unsure on its feet, with a trio, again, that needed more contrast to stand out appropriately. The finale sounded much better-rehearsed than the first three movements, and it ended the piece with a good helping of Haydn’s celebrated wit.

Schubert’s Quartettsatz (in C minor, D. 703), which followed, also shortchanged the music somewhat, with the musicians playing cleanly and attractively, but not taking advantage of the subtler aspects of Schubert’s writing, such as the little key-shifting triplet motif that recurs throughout, and which cries out for some emphasis and shade.

The concert ended with a lush William Zinn arrangement of Bess, You Is My Woman Now, the duet from George Gershwin’s opera Porgy and Bess. It was lush and lovely, but also could have used some more shape, perhaps most notably at the harmonic change that accompanies the bridge section beginning But I ain’t going.

The Delray String Quartet will repeat this program at 8 p.m. Friday night at All Saints Episcopal Church in Fort Lauderdale, and again at 4 p.m. Sunday at St. Stephen’s Episcopal Church in Coconut Grove. Tickets are $20. Call 213-4138 or visit www.delraystringquartet.org.

***

The Boca Raton Symphonia entered the Saturday lists as part of its first-ever two-concert weekend, and opened it with the first hearing of a new work by the retired orchestra executive who helped found the group seven seasons ago.

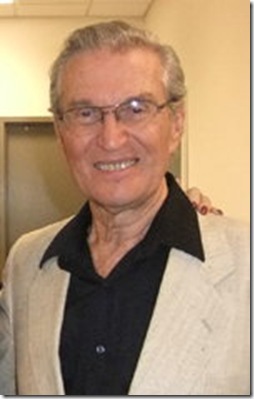

Marshall Turkin, who turns 86 this year, began his professional career as an arranger for the U.S. Navy while stationed at the Panama Canal during World War II, and then pursued life as a composer and jazz musician in New York thereafter. Life intervened, as it often will, and Turkin, who went on to lead the Pittsburgh and Detroit symphony front offices, took a hiatus of more than 50 years from his composing before returning to the multi-staved paper in 2010.

Turkin’s Five Brief Essays on One Theme turned out to be a well-crafted, skillfully orchestrated work in a style congruent with the Americanists of the last mid-century, and for me evoked writers such as Norman Dello Joio, Paul Creston, and David Diamond. The theme, taken from a piano piece Turkin wrote in 1954, had an attractive, searching quality, and the composer did some interesting things with it. The third essay, A Dream, contained a warm, engaging trumpet solo, and the fourth, A Joke, is a swift, sparkling movement that showed off Turkin’s knowledge of orchestral resource as lines went rippling through the instrumental fabric.

Several things to note: One might have expected a man in his mid-80s to write a nostalgic, syrupy piece that would have gone straight to the psyches of the older members of his audience, but he pointedly avoided that, much to his credit. Second, the piece is a little too brief, especially A Joke, which is far too short, and has plenty of material that could easily be expanded.

The third is that Turkin’s position as the founding president of the group surely helped win him the spot on the program, but he has written a real piece of music here, one that might have seemed quite retro only 30 years ago but whose language is now in step with its time. He has written another piece for the Festival of the Arts Boca (the Boca Fest Overture, set for debut March 14), and a perusal of the score shows its speech to be along the same lines, and also well worth a listen.

The bottom line here is that while the Five Brief Essays could be said to come out of a late-life hobbyist impulse, this is not the music of an amateur. Turkin was trained in composition at Northwestern, and by the evidence here, he must have been a diligent student.

But the concert Saturday night at the Roberts Theater at St. Andrew’s School also stood out for another reason: the pianism of Alex Kobrin. After the Turkin piece, Kobrin took the stage for the Beethoven Fourth Concerto (in G, Op. 58). A Van Cliburn Competition gold medalist in 2005, the Russian-born pianist now teaches at Columbus State University in Georgia and concertizes around the world.

But the concert Saturday night at the Roberts Theater at St. Andrew’s School also stood out for another reason: the pianism of Alex Kobrin. After the Turkin piece, Kobrin took the stage for the Beethoven Fourth Concerto (in G, Op. 58). A Van Cliburn Competition gold medalist in 2005, the Russian-born pianist now teaches at Columbus State University in Georgia and concertizes around the world.

Kobrin played this great work with an exceptional level of polish, every phrase carefully considered and buffed to a high sheen, and at the same time, he was fully alive to the nobility of the concerto. This is not a concerto with obvious fireworks; it’s more of an exercise in delicacy, tone color and melodic beauty than showboating. That requires a pianist with a strong sense of this work’s special, fragile balance, and in Kobrin, the Boca Symphonia had it.

The famous piano-only opening of the concerto, so daring and different from the usual contemporary model, was a statement of surpassing gentleness and intimacy in Kobrin’s hands, and it marked much of the future dialogue with the orchestra. Guest director Arthur Fagen had a better version of the Symphonia to work with here than music director Philippe Entremont did in the first concert of the season, primarily in that Fagen had a far stronger complement of violins.

Kobrin unleashed impressive athletics in the explosive cadenza of the first movement, one of the few moments of straight-ahead virtuosity in the piece. In the question-answer dialogue of the second movement, Kobrin played with exceptional poise against the peremptory drama of the strings, and in the finale, he again demonstrated a level of control in which rhythms were crisp and exact and runs glittered and gleamed. A lovely performance by a very fine pianist, and which might have been improved only by a slightly more aggressive, vigorous approach in the finale.

To close the concert, Fagen led the Symphonia in the Symphony No. 3 (in A minor, Scottish) of Felix Mendelssohn. A repertory work, but one that gets far less frequent outings than its Italian-themed sibling, and it was good to hear it. The orchestra gave it a decent reading, too, with a bubbly second movement (nice clarinet work here by Michael Forte) and good ensemble work throughout.

And that was the primary accomplishment; with a better string section, this orchestra sounded much more impressive. Fagen, a fine conductor, sounds as though he did some good drill work with the sections, and the result overall was a satisfying and often exciting concert for the group’s second seasonal outing.