Whimsy and wonder dominate in the world that Robert Vickrey creates in his painting. On first glance, there’s not much that is dark or foreboding. In fact, within moments of entering the exhibit, Robert Vickrey: The Magic of Realism, now on view at the Boca Raton Museum of Art until June 19, one feels, well, comforted.

And that’s because the symbolic images are reassuringly familiar. Look around. There are nuns and children and balloons and bubbles and sparklers and bicycles and lions and tigers and bears. Oh my, scratch that last part. There are no lions or bears, but there is, actually, a tiger (Tiger, Tiger, 2009). And, overall, what there is, resoundingly, in Vickrey’s work, is a sense of safety associated with childhood. That quality makes this exhibit remarkably soothing to the soul — at the surface.

It makes it remarkably good, too, as a family-friendly exhibit. The subject matter, symbolism, and references to great artists serve as a good launching pad for talking to children about art. Yet as quickly as one decides that these paintings are simply beautiful, something might seem equally off.

Vickrey works in a style, as the show’s title suggests, known as magic realism. It’s a style with roots in pre-World War II Germany and is built around the idea that beautiful things are not always what they seem. Another artist known for this style is Andrew Wyeth, and his seminal work, Christina’s World, is the quintessential example of something that appears beautiful at first glance, yet has disturbingly melancholic undertones.

The same can be said of many of Vickrey’s works, though the sadness is not quite as deep. Both also chose egg tempera as their signature medium and this explains the striking similarity in many works.

One such example is Bubbles (1976), which seems an allusion to Wyeth in its color palette, lighting, and the partial inclusion of a window. In it a girl concentrates on blowing a bubble. She holds the type of bubble dispenser we’ve all used, so the emotional connotation with that object is pleasurable familiarity. The room is already filled with bubbles and this gives the impression she’s been at it for a while. As if the girl and the bubbles weren’t charming enough, there’s a kitten staring down at her from the windowsill. The girl is lit from above, like an angel, common throughout Vickrey’s painting. For him, children are angelic.

Yet, just as you’re about to lapse into a Hallmark-moment trance, something strikes you as odd and it’s not simply this painting, in and of itself. It’s this painting juxtaposed against an exhibit full of similar paintings of similar children engaged in similar activities. Suddenly, you may feel trapped in a world that’s comforting and safe because there’s no place else to go. And that’s when you realize you’re viewing transitory innocence, a dream that fades with age.

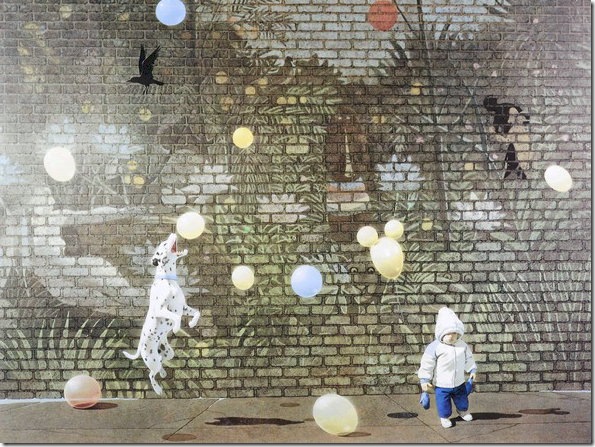

Perhaps that’s why there are brick walls throughout Vickrey’s work, to represent a barrier through which naïve fascination can’t pass. In Midwinter Dream (1984), a toddler stands near a brick wall while balloons float about him. Nearby a dog jumps up and tries to grasp one. This child, like the girl in Bubbles, seems trancelike. The image of Henri Rousseau’s final painting, The Dream, is painted on the wall. The Dream is a work that juxtaposes symbolic objects against those that are out of place. What does it mean to have one dream juxtaposed against another?

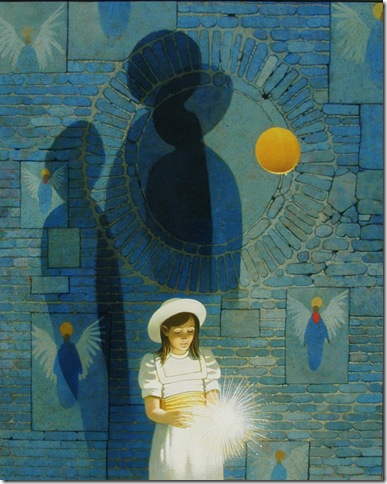

In Lacy’s Sparkler (2008), a young girl holds a sparkler – the kind given to children on the Fourth of July. She also stands in front of a brick wall on which images of angels floating heavenwards appear. This time the light seems to come from below and casts an interesting tri-shadow on the wall behind her. Like all the children here, she is expressionless, but appears engrossed in watching the sparkler.

Vickrey discovered, and adopted the egg tempera painting technique while getting his MFA at Yale. Egg tempera paint doesn’t yellow like oils, so it retains clarity of color and it also lends itself to being slightly easier to use than oil for painting fine details. There’s translucence because you can’t build layers as you can with oils or acrylics.

He worked, primarily, as an illustrator for Time magazine where he painted over 70 covers of influential people, including a 1961 portrait of author J.D. Salinger that was hung last year in the National Portrait Gallery.

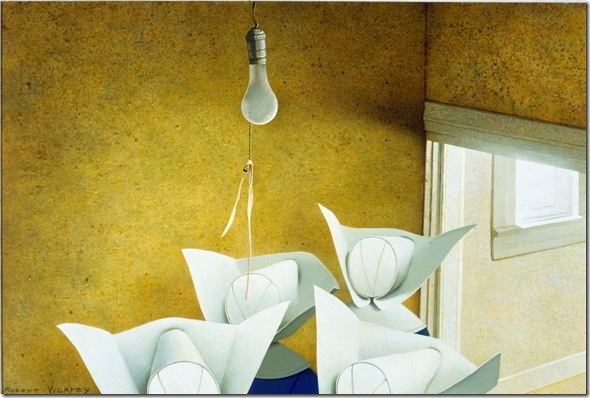

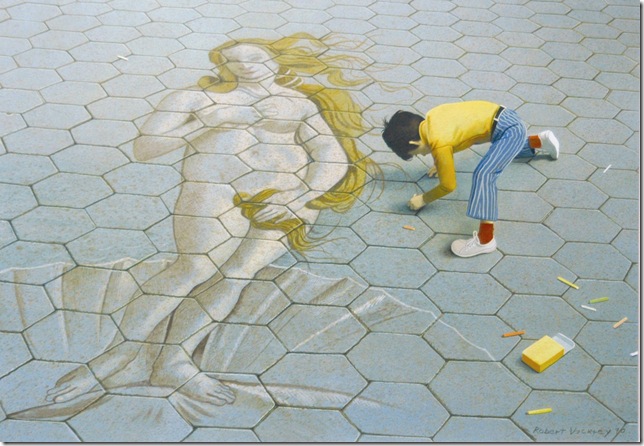

Clearly, in his fine art, he was compelled to make a statement about childhood as a symbolic time in life and to pay homage to other artists. There are references throughout his work to specific classic works, such as in Clam’s Eye View (1990) and Homage to Chardin (2011) where he recreates Sandro Botticelli’s Birth of Venus and Jean Siméon Chardin’s Soap Bubbles. In both, children are, again, engrossed in activities that children do – drawing, blowing bubbles.

Not all of Vickrey’s works deal with children, however. He was equally fascinated by an order of nuns that originated in Paris in 1935 know as the Daughters of Charity of St. Vincent de Paul. They are the subject matter of the most beautiful and interesting works in this exhibit, including Sea Breeze (1985). The colors, perspective and lighting evoke images by Giorgio DeChirico, and it appears that Vickrey was influenced by De Chirico who originated a realistic style with sinister undertones.

One of the nice aspects of the Boca Raton Museum of Art is that the layout provides an opportunity to stand in the center of an exhibit and do a 360-degree scan of the entire gallery. It’s really helpful to view Vickrey’s work comprehensively because, overall, while there are allusions to De Chirico and Wyeth, Vickrey’s work is not quite as dark or disturbing as either of those artists. Rather it presents a transitory world that has an inherent sadness because childhood is ephemeral. And while the end of childhood represents the end of innocence, it’s not as much tragic as disappointing.

In commenting on the nuns as subject matter, Vickrey revealed a fascination for what is delicate.

“I was interested in the abstract shapes of the cornettes (their headdresses). These figures were becoming a symbol of something too beautiful and fragile to exist in our modern world.”

Throughout this exhibit, symbols of “fragility” are what binds each of Vickrey’s works to the other and tells the visual story of an artist enamored with respite, with creating a world shielded from the irredeemable, brute facts of life. A world where children are engrossed in play and nothing bad will happen, but where it’s clear that danger is lurking.

Robert Vickrey died just a few days before this exhibit began, at his home in Naples, on April 17. He was 84.

Jenifer Mangione Vogt is a marketing communications professional and resident of Boca Raton. She’s been enamored with painting for most of her life. She studied art history and received her B.A. from Purchase College.

Robert Vickrey: The Magic of Realism is on view at the Boca Raton Museum of Art until June 19. Hours for this exhibition are Tuesday through Friday from 10 a.m. until 5 p.m. Saturday and Sunday from 12 p.m. until 5 p.m. On the first Wednesday of the month, the museum remains open until 9 p.m. Admission is $8 for adults, $6 for seniors, and $4 for students. For more information call 561-392-2500, or visit www.bocamuseum.org.