By Márcio Bezerra

Sublime. Nothing short of sublime. That sums up the concert presented by the Vienna Philharmonic for the Classical Concert Series at Kravis Center for the Performing Arts.

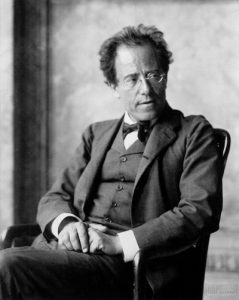

Playing for a nearly sold-out audience, the venerable ensemble, in its first-ever appearance in South Florida, gave a heart-wrenching performance of Gustav Mahler’s Symphony No. 9, his final complete work.

Notwithstanding any reservations one may have about associating the output of a particular composer with his or her private life, it is difficult to avoid thinking about the Ninth as a farewell piece, in which the composer’s preoccupation with the meaning of life, death, fate, and spiritual transcendence comes to the fore in explicit sonic ways.

Take for instance the main motive of a descending major second heard in the opening. Borrowing from the minor second traditional sighing figure (used by composers since the Renaissance), it becomes a more accepting sigh, as if Mahler is looking back at his life and saying “Well, that was all…”

Acceptance turns quickly into violent outbursts of anger and confusion, and the Vienna Philharmonic interpretation of the sprawling first movement accentuated the edginess of the score.

Conductor Franz Welser-Möst directed the orchestra passionately throughout the four movements.It was quite a contrast from his appearance with his own orchestra (Cleveland) a little over a month ago. Gone was the aloofness that characterized his reading of Prokofiev’s Fifth Symphony in January.

The freedom he gave to the musicians in the second movement was a kind of mutual understanding and trust that is rarely achieved by orchestras and guest conductors.

He also was able to control the unpredictable audience of Dreyfoos Hall, which did not applaud between movements, even after the big final bang of the third movement Rondo-Burleske.

His reading of the final Adagio reached a transcendental level. Steadily moving forward, his control of dynamics and voicing was remarkable. He kept the audience in suspense for some seconds after the final note, only to have a cellphone alarm ring before applause. It was the kind of juxtaposition between the sublime and the banal that Mahler so often indulged in.

This was probably the most memorable evening of classical music ever witnessed by our local audiences, at least since Leonard Bernstein brought the New York Philharmonic to the Flagler Museum in 1969.

One wishes that moments like those would become more frequent, but the fact that they are not, makes them even more special. It was an honor to be part of this experience.