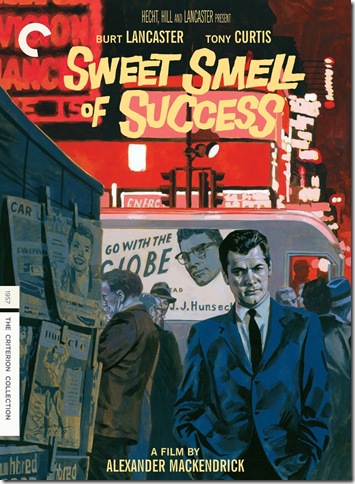

Sweet Smell of Success (Criterion)

Release date: Feb. 22

Standard list price: $21.99

Ahead of its time in 1957, Sweet Smell of Success is, like Billy Wilder’s Ace in the Hole, one of Hollywood’s most sordid exposes of the entertainment/media complex. It dismantles the promotion industry as an intractably corrupt system, while tapping into deeper, more sinister subtext in every nook and cranny.

Burt Lancaster, starring as a Walter Winchell surrogate named J.J. Hunsecker (one of the best monikers in screenwriting history), oozes menace and power – a soft-spoken sociopath with a bullhorn reaching millions. Like Winchell, Hunsecker writes a daily newspaper gossip column that can skyrocket to fame the people he publicizes or break the careers of those he derides with his acid pen. He is as close to as the nation’s entertainment sector has to a king, even if his monarchy is corrupt and his minions despicable.

Lancaster’s deliverance of one of the film’s famous lines – “I love this dirty town” – is convincing in its noirish cynicism. Shooting on real New York City streets at a time when studio backlots were still the standard operation procedure, director Alexander Mackendrick realizes Hunsecker’s declaration, both in the physical filth of the on-location realism and the mental, emotional filth of its protagonists.

Hunsecker was voted one of the AFI’s top 50 movie villains of all time, but his industry compatriot in the picture is almost as vile. Tony Curtis plays Sidney Falco, a guttersnipe press agent who, like most of this film’s denizens, is only it for himself. To get back into Hunsecker’s good graces – and guarantee his upset clients the ink they desire – he agrees to plant a smear in a rival newspaper column about Hunsecker’s sister’s latest beau. The poor boy seems to be an upstanding gentleman, playing in a popular New York jazz band, but Hunsecker seems to have it bad for his sister; at least as bad as a screenwriter could get away with in ‘50s Hollywood.

While most of the significant players in Sweet Smell of Success are appalling, the incestuous lust Hunsecker harbors for his sister – whom he treats the way a lecherous father might – makes him much more repulsive than the run-of-the-mill leeches puckering his posterior for a column inch. And it makes for a fascinatingly subtextual film, bubbling with unspoken depravity underneath the already grimy surface.

Criterion’s exhaustive double-disc release of the film analyzes it from every angle – historical, trivial, formal, theoretical. The luminous chiaroscuro lighting that makes New York feel so alive in this picture is given a flawless transfer, as well as its own bonus featurette on the craft of cinematographer James Wong.

The supplemental disc has four features total. The 1986 documentary Mackendrick: The Man Who Walked Away looks at the director’s ascent from graphic illustrator and adman through the top ranks of Britain’s esteemed Ealing Studios and finally on the streets of New York, making this progressive masterwork. In a new video interview with director James Mangold (most recently of Knight & Day), who took a film course under Mackendrick’s mentorship, Mackendrick is revealed to be an astute film mind and an Aristotlean philosopher of narrative.

And finally, Neal Gabler, author of Winchell: Gossip, Power and the Culture of Celebrity, offers a brief, compelling history of Hunsecker’s inspiration, and particularly on the differences between the populist Winchell and Lancaster’s more elitist interpretation. According to Gabler, the specific story that inspired Ernest Lehman’s script for Sweet Smell was a lot more interesting and eccentric than the tame onscreen enactment.

In real life, it was Winchell’s daughter, not his sister, that he was “protecting,” and the man she was romancing was not a fresh-faced jazzman but a Broadway hustler out to get Winchell’s money. So Winchell had his daughter committed to a mental hospital and used his considerable influence to convict the boyfriend to 18 months in prison for not claiming $4,000 income on his taxes.

By Gabler’s account, the real wheeling and dealing of this larger-than-life media personality is indeed more interesting than Hunsecker’s quid pro quos – proof, once again, that truth remains stranger than even the most imaginative fiction.

Promised Lands (Zeitgeist)

Release date: Feb. 15

SLP: $27.49

Promised Lands is writer Susan Sontag’s only documentary, shot in Israel during and immediately after the 1973 Yom Kippur War. Influenced more by Jean-Luc Godard’s oblique essay films than the Maysles Brothers’ fly-on-the-wall observations, Sontag’s film ignores most documentary-film protocol in a directionless portrait of a tenuous nation. She lingers contemplatively on daily life in the Holy Land and conveys the history of the young nation not by rote recitation of key events but by the silent filming of wax-figure recreations at the Israel Defense Forces History Museum. Refreshingly, the movie is absent ideological pandering; it’s obvious that propaganda cinema was the last thing on Sontag’s mind. But it’s frustrating that Sontag declines even to identify the supposed experts she interviews for the film’s narration and, without the benefit of a structure, the viewer is simply taking in isolated vignettes that strive for coherence. The best segment finds Sontag filming a sort of kamikaze hypnosis by an unorthodox Israeli psychologist on a shell-shocked soldier. The poor man is terrorized to within an inch of his life by a programmed sensory assault that is difficult to watch.

Birdemic (Severin Films)

Release date: Feb. 22

SLP: $22.49

Birdemic has been labeled, both derisively and affectionately, as this generation’s Plan Nine From Outer Space. But this completely inept, Z-grade “horror” feature makes Ed Wood look like John Ford. It doesn’t sound totally awful on paper; it’s about a pack of eagles and vultures that attack a small town in Silicon Valley, where a software salesman and an aspiring model are beginning a romance. But the torture here is in the technique, not the story. As far as staging goes, all the invisible “lines” are ignored and crossed, with awkward results. There is no blocking, and no continuity between edits – a scene will be sunlit in one cut, dark in the next and back again. The dialogue is smothered by nature’s ambient noise. The tripodless camera wanders for no apparent reason. The acting is an insult to cardboard. The film plays out like Hitchcock’s The Birds if it was directed by someone who had never seen a movie before – or by a seasoned hand who set out to deliberately break every rule of basic film grammar as a way of subverting convention. Interviews with writer-director James Nguyen suggest he is most definitely not the latter. You’ll be laughing at this film, not with it, but either way, it’s a movie destined for cult success. God help us, there is already a sequel in the works, in 3D no less.

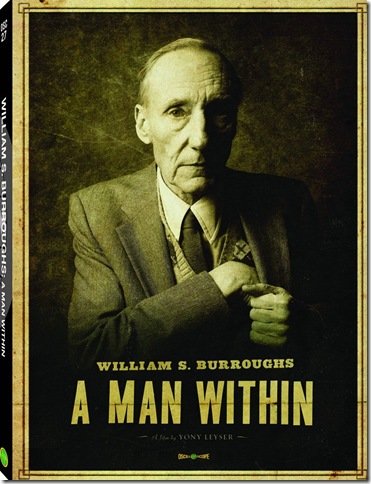

William S. Burroughs: A Man Within (Oscilloscope Laboratories)

Release date: Feb. 15

SLP: $23.99

Oscilloscope Laboratories has released its second DVD of the year about a Beat writer, but compared to the formerly audacious Allen Ginsberg collage Howl, its new William S. Burroughs documentary is downright conventional. And there’s nothing wrong with that when the subject matter is so compelling. Director Yony Leyser does a fine job of pinpointing Burroughs’ contradictions as both a left-wing, gay, countercultural rebel and a model NRA member, obsessing over firearms and sleeping every night with a loaded gun (he would later accidentally kill his wife Joan with a gunshot to the head). Leyser also reveals the impact Burroughs had on other art forms – he is credited for the origin of the terms “blade runner” and “heavy metal.” Sonic Youth scored the documentary, musicians from Frank Zappa to Kurt Cobain are shown snapping photographs with Burroughs, and filmmakers as wide-ranging as John Waters and Gus Van Sant pontificate about his influence. That being said, the movie could have gone further into Burroughs’ literary contributions and what made his books so admired besides their status as censorship magnets.