It’s not easy to categorize a musician who can write sonatas for turntables and hip-hop etudes, a violin concerto and dance scores, but the world of contemporary classical music is quickly getting used to the cross-genre fluency of people such as Daniel Bernard Roumain.

“I think there are a lot of composers my age and younger, who literally have played in rock bands, go to nightclubs, kind of hang out in what you could loosely describe as anti-classical music establishments,” Roumain said. “And I think that it’s reflected in what we’re all doing. There’s a whole scene of young American composers who freely embrace technology, work with rock musicians, work with DJs and laptopists … and who are also electronic musicians and remixers, and are adept at the handling of the technology.”

Now, with his custom-made six-string violin (whimsically named Bernadette), Roumain is pursuing a multi-pronged career that sees him as composer, performer, bandleader, teacher, and conductor, a far cry from the regimented concert life he once thought he would be leading when he first heard a violin in the halls of Margate Elementary School and knew what he wanted to do for a living.

Roumain, 39, grew up in Margate as the son of Haitian immigrants who moved from suburban Chicago to Broward County when Daniel was just 5. After graduating from the Dillard School of Performing Arts in Fort Lauderdale, it was off to Nashville for study at Vanderbilt University, then north to Ann Arbor for a master’s and doctorate at the University of Michigan.

Since then, he’s held enviable compositional residencies at prestigious organizations such as the Orchestra of St. Luke’s, the American Composers Orchestra and the Seattle Theater Group, and schools such as Arizona State and Drexel universities. He’s written for theater, film and television, and for world-class instrumentalists such as guitarist Eliot Fisk, who in 2007 premiered Roumain’s guitar concerto, We March!, with the Stuttgart Chamber Orchestra.

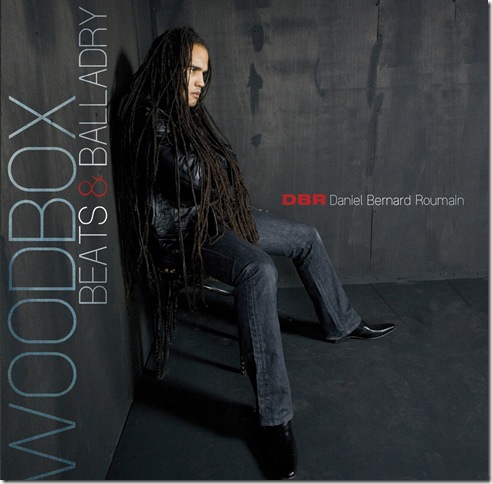

In late March, Thirsty Ear Records released Roumain’s second album, Woodbox Beats & Balladry. It contains music Roumain has written over the past three or four years, and unlike his first album, etudes4violin&electronix, released in 2007, Woodbox was designed to be a showcase for his nine-piece band.

“It’s always about the violin first, and it’s always about a conversation,” he said. “The first record was a conversation with other composers – Philip Glass, [Ryuichi] Sakomoto, [DJ] Spooky, and so forth – this is really a conversation with the members of my band, DBR and the Mission. It’s [also] kind of a conversation between my violin as performer, and my work as a composer.

“We focused on works that were written down – very little improvisation, including the ‘Sonata for Violin and Turntables’ — and really the conversation had to do with musicians I’ve been working with for years,” he said. “And the compositions we’ve been playing for years. So this is something that’s much deeper, much closer to home, and I think the record reflects that.”

Woodbox Beats & Balladry is an energetic, eclectic mix of music that makes use of radically different sound worlds: from the chugging rhythms of Armstrong (based on one of Roumain’s Hip-Hop Etudes) to the moody stasis of Simone, with its long, simple piano chords and a melody that climbs by repeated notes slowly up. Although Roumain’s widely varied violin playing stands out as the focus of the disc, it still has the feel of a band record on its dancier cuts [here is the official trailer for the disc].

But there are also tracks such as Moonshine, for which Roumain did “everything: the production, the keyboards, the track, the bass – and that’s just not unusual at all anymore.”

“There’s a really big difference between the previous generation of composers, who were more about ensemble work, and who were maybe less comfortable with some aspects of the technology. Maybe that’s a fair argument, I don’t know,” he said. “But certainly what’s happening now is you’re seeing composers who have huge interest in film, television and the dance scene, and the rock hipster scene, the indie scene. I think all this is finding its way into their voices.”

The final track on the album, Our Country, is a deeply expressive meditative fantasy on My Country, ‘tis of Thee, in which the familiar tune is played and then varied in gradually higher registers, most of it over a gentle ostinato pattern in the piano. The piece begins in the lowest strings of the six-string, and it sounds very much like a cello. The violin was made for Roumain by Eric Aceto, a luthier who owns Ithaca Stringed Instruments in upstate New York.

“I’ve been working with him for a few years, and we started talking casually about ‘How can we make a violin that has very low strings? What would we have to do to make it really sound good?’” Roumain said.

The violin has two added strings on the lower end, a C below middle C (like the lowest string of the viola) and an F below that. Roumain said he sometimes tunes the bottom two strings to E-flat and B-flat and explores the resulting chord, a nice, jazzy E-flat with a major seventh and a flat fifth and ninth.

“It’s the only instrument of its kind in the world. It has a very unique sound,” he said. It’s also heavier, like a viola, and there was some learning curve for Roumain to get comfortable with it. “The first few months, I was getting this weird tennis elbow … It’s a monster. It’s not something you just pick up and play.”

Roumain, like many musicians of his generation, is working at a time of great change. The advent of relatively cheap but excellent computer technology has radically altered the music industry from the standpoint of recording and distribution. It also has encouraged compositional efforts from writers who until relatively recently would have had little chance of getting a hearing for their music.

“I’m not sure, but I would imagine there’s never been more composers living and working in New York,” said Roumain, who also lives there with his wife, Jill, a special education teacher, and their 11-month-old son, Zachary. “At the same time, it doesn’t necessarily feel that way … The people getting the attention don’t necessarily reflect not only the vastness of the industry, they also don’t necessarily reflect the depth or even the interests of the industry.”

Still, while the tendency of cultural activity to organize itself into hierarchies of “in” composers and players hasn’t changed, almost everything else has.

“The biggest change is you do have access. Composers do have their own websites, they do get their music out over the Internet, they do have their own online mechanisms, not for publication, but for performance,” he said.

“I think that for me, I’m always thinking about what I want to do next … You’re kind of always competing, not only with yourself in a way, but the people who came before you, the people right next to you, and the people coming from behind,” Roumain said.

“I think that’s also a big difference. John Cage didn’t have to compete with a 16-year-old who has 200,000 views on his website.”

Much of Roumain’s work life is taken up with education. He has just finished a year of occasional stops at Vanderbilt as a visiting associate professor of composition, and during a recent appearance in Boston, he toured six schools in the Massachusetts capital. The chief question he gets from aspiring musicians is this: How do I do what you did?

When they ask, Roumain tells them who his models were: Philip Glass, Prince, Madonna, Nina Simone, Thelonious Monk, among others. “And sure, I definitely have a whole list of activities, my kind of Ten Commandments for a career, and I just try to give them very practical, specific guidance.”

Roumain also defines himself as a Haitian-American artist, and he remains passionate about aiding his parents’ native country, especially in the wake of the Jan. 12 earthquake that killed an estimated 230,000 people.

“Every opportunity I get I’m flipping my previously scheduled concerts into relief efforts,” he said. “I think, moving ahead, it’s my job as a self-proclaimed Haitian-American composer to just keep talking about it, to remind people that Haiti still needs help.”

Roumain will visit Haiti this summer with other artists to give some concerts, and he notes that music has the power to bring people together. “The thing about a concert, or the arts, is that it really gives you a sense of your humanity,” he said, and he hopes the music will help Haitians who have lived through such a punishing catastrophe be reminded of their humanity as well.

One major event still to come this year is scheduled for Sept. 25, when the New World Symphony in Miami Beach will give the premiere of Roumain’s new Symphony for Dancers, Dreamers and Presidents, written for the Sphinx Foundation, and scheduled for performance by 11 other major symphonic ensembles including the Detroit, Philadelphia and Cincinnati orchestras. Roumain has written a good deal of music for dance, having worked for six or seven years with the eminent choreographer Bill T. Jones, and plans to soon release a recording of some of that music.

“I have found a way to make all of these endeavors have a fluid and effortless conversation with one another,” he said. “And that’s good for me. If you talk to my wife, I tour too much; if you talk to the band, we don’t tour nearly as much as we should.”

Most recently, last month he led the New England Conservatory of Music student orchestra in his new Symphony for the Dance Floor, and he’s begun work on another commission for the Brooklyn Academy of Music.

Despite all these different activities and the relentless pace of change in the industry, certain things about an artist’s life are the same as they ever were, Roumain said.

“Changes involve a hyper-branching out of many different things at once,” he said. “The only thing you can do as an artist, the thing that has not changed at all, is that you have to know who you are, you have to understand your audience, and you have to build it and cultivate it every single day.”

“In that sense, nothing has changed,” he said. “The commitment – that hasn’t changed at all.”

Daniel Bernard Roumain’s website – www.dbrmusic.com – has a large selection of sheet music excerpts from his compositions, which helps gives visitors a better idea what his music is all about.