In a time calling for simplicity and scaling back, portraits of the complete opposite score well.

Only hours into their first day at the Flagler Museum, freshly hanged paintings of European and American extravagant interiors already were having an impact. The first visitors found them gorgeous, informative; even inspirational.

Impressions of Interiors: Gilded Age Paintings by Walter Gay, had been in the works for several years when it opened last October at the Frick Art Museum. The Flagler is the second and last stop of this extensive show featuring works from private collectors and institutions including the Musée d’Orsay, the Art Institute of Chicago, the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston and the Metropolitan Museum of Art. The Frick and the Flagler both have the kind of lavish decorative interiors that became Gay’s famous subject.

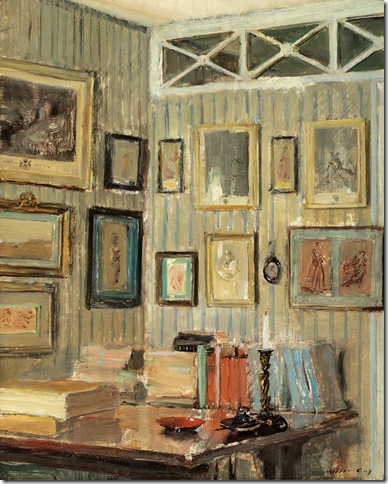

The exhibit, running now through April 21, includes 67 paintings, watercolors and photographs as well as excerpts from his wealthy wife’s diary. It emphasizes the artist’s personal touch and moves away from the notion that he was simply copying what he saw. From the beginning, we can see Gay’s tendency to revisit the same subject matter and his preference for rooms devoid of a physical human presence.

The Sculptor’s Studio (1885) shows French sculptor Jean-Louis Gregoire hard at work in an environment he must know well by now. A plaster sculpture sits nearby. We sense he has been there for a long time. Three years later the sculptor is nowhere to be found on a painting exploring the same space: A Sculptor’s Studio. This time, the title is less personal. However, the painting has more confidence. Gay places a greater trust in the viewer. He knows that we will understand it: The French sculptor is not really gone. He has just stepped away momentarily. A door has been left open after all, and he is bound to emerge from the dark back room any minute now. His tools have been left on the floor and there is that expressive sculpture sitting uncovered. Would he not have placed a cloth over it if he did not plan on returning?

Some of Gay’s early works do represent peasants, factory workers and everyday life, but even these have signature elements found in his later pieces: the use of light to draw the viewer into the picture and the unexpected cropping of the frame, as if it were a cutoff photograph. The show contains plenty of examples of both. They are easy to spot, if you take your time.

With each piece, there is the distinctive feeling his empty rooms are inhabited.

“Traces of humanity,” is how Chief Curator Tracy Kamerer calls the little clues Gay left us. An overstuffed armchair, an open window, a pile of books and the food left on a dining table are not meaningless details. They are placed there for us to feel welcomed, comfortable, relaxed. It is as if the artist felt the need to clarify these are not frigid cold rooms. There is life in them.

Thanks to photographs of the time and documented accounts, we now know the Massachusetts native, who lived in Paris and studied with Toulouse de Lautrec’s teacher, was not just reproducing these sumptuous interiors on a canvas. Instead, Gay exaggerated the size of objects, rearranged pieces of furniture and approached a view from different angles.

“In some cases, improving them,” said Kamerer.

The Old Fireplace (Chateau de Fortoiseau) and The Ghost Room supposedly feature the same space except they are completely different. Only the angle is the same. In both cases we stare at a fireplace. White-and-blue Chinese vases and a dark clock rest on top of the first while the other one supports fresh yellow flowers, a glamorous golden clock and a red book on the right corner. The fireplaces themselves differ in style: one is stripped from adornments while the second one is made of marble. Each is accompanied by a chair, also not the same. In The Old Fireplace, the room is brighter and the mirror reflects an open door.

Another work where we can assess these intentional discrepancies between an actual living space and Gay’s version of it hangs in the last gallery room. It is a painting focusing on his brother’s home: The Music Room and Dining Room of Eben Howard Gay’s House (1902). If you look closely, you will notice the Chinese vase appears larger on the painting. Gay has also replaced the card table with a Chippendale-style double chair.

“He was making choices,” said Kamerer.

Many years after making them, his choices still influence the way we perceive these elaborate interiors with their ornate paneling, tapestries and 18th-century French furniture. Gay wanted to convey the essence of a room. His wife, Matilda, called his paintings poemes d’interieurs.

A depiction of the library room at his Chateau du Breau (of all the places he lived, this one inspired the greatest number of works) comes across as too formal and serious, therefore making us distant and cautious. A close-up version of it, also in the second gallery room, narrows down the view of the library room instead of giving us the broader picture. In doing so, the room feels cozier, more intimate and personal.

In some works, he focuses less on the furniture and more on the actual open space. In others, such as Interior of the Bedroom of the Chateau du Breau (c.1912), the light is the main character.

Often, Gay is unfairly perceived as old fashioned, Kamerer said. In fact, his compositions, often diagonal and seemingly cut-off, suggest a much modern painter. He was riskier than other artists of the time and, unlike them, Gay considered watercolors to have their own merit. For him, watercolors were not mere studies leading to a masterpiece.

In addition, the exhibit does a good job of hinting at the interesting associations between Gay and leading contemporaries, including Edith Wharton, Auguste Rodin, John Singer Sargent and Edgar Degas.

It is pretty and historically valuable, although the opulence portrayed is a bit hard to swallow. Even Gay’s poetic intention of evoking the spirits of the empty rooms seems at times shallow and superficial. But considering the times, I think this is a normal reaction.

Impressions of Interiors: Gilded Age Paintings by Walter Gay is on display at the Flagler Museum, Palm Beach, through April 21. Regular ticket prices: Adults: $18; $10 for youth ages 13-17; $3 for children ages 6-12; and children under 6 admitted free. Hours: 10 am to 5 pm Tuesday through Saturday, noon to 5 pm Sunday. For more information, call 561-655-2833 or visit www.flaglermuseum.us.