It says something important about the connections our area arts leaders have in that for the last concerts of the season for the Symphonia Boca Raton, the orchestra was able to feature one of the leading pianists of the older generation and an encore appearance by one of the country’s most intriguing conductors.

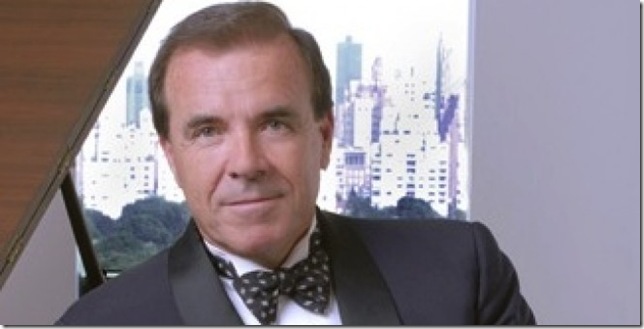

The final Symphonia Boca Raton concert of its Connoisseur Series took place Tuesday night at the Eissey Campus Theatre in Palm Beach Gardens, and featured the pianist Misha Dichter in the Beethoven First Piano Concerto as led by former Seattle Symphony conductor Gerard Schwarz.

It was a thrill to see Dichter, who at 70 is a living link to the great Romantic school of piano playing as handed down by one of his teachers, Rosina Lhevinne, and the German-Viennese tradition he imbibed from another teacher, Aube Tzerko, a student of Artur Schnabel. I’ve always enjoyed his Classical side best, but overall it’s just good to see him still out on the road performing, especially given the hand surgery he had to undergo a few years back to save his career.

Thankfully, it was successful, and there was ample proof in the Beethoven concerto. All of the five Beethoven concerti are masterworks of varying degrees, and the First (which is really the Second in order of composition) has a wonderful feeling of freshness and muscularity that’s hard to resist. And Dichter didn’t make it any easier: This was a most engaging reading of this work, with a sense of nobility and good taste that amply fulfilled the composer’s intentions.

Dichter’s playing sounded big and full throughout the concerto, and his fingers were fleet and accurate, with only a couple exceedingly minor smudges. From a first entrance that was striking in its confidence, and which sounded especially so given that the Symphonia is a chamber orchestra of 35 players. For the first cadenza, Dichter unleashed his second side, with a fiery, expansive cadenza in which the pianist seemed to relish the most dramatic gestures of this particular solo display.

In the second movement (Adagio), Dichter imparted a good deal of warmth to the main theme, which looks back to Haydn and Mozart in its air of formal sentiment. And in the finale, Dichter sparkled in the high-spirited, surprise-laden themes, and in the cadenza again let loose some Romantic-era fire. It was a fine performance overall, and the audience at the Eissey was vociferous in its applause (though that did not win them an encore).

The orchestra, which partnered ably with Dichter, nevertheless sounded somewhat rough at the edges, perhaps in part because many of the players on stage were not same ones that constituted the Symphonia in earlier concerts, being otherwise occupied in the pit for Palm Beach Opera’s Ariadne auf Naxos.

Now with 10 years under its belt, the Symphonia should be considering whether it’s feasible to have a core ensemble rather than having to restaff for schedule conflicts. In any other area of the country, that might seem to be stating the obvious, but here in South Florida, the reality is that many gigging classical musicians must chase work up and down Interstate 95 to perform in the many part-time musical organizations from Miami-Dade County to the Treasure Coast.

That affects the quality of the music from concert to concert, making it inconsistent, even with fine players brought in to replace the more-or-less regular members. Here’s hoping the Symphonia can find enough money to secure the core of an ensemble that will stay from year to year, even when the concert schedule stays largely part-time.

Schwarz has long been a champion of American music and certain of its composers, particularly David Diamond, whose birth centenary was last year, and whose Concerto for Small Orchestra he has programmed for his return to lead the Symphonia a year from now. On Tuesday’s concert, he conducted one of Charles Ives’s best-known pieces, The Unanswered Question.

This short, brooding piece, in which strings solemnly play quiet chords as winds and a solo trumpet trade question and answer, was marred somewhat by repeated loud door openings and closings in the hall for people returning late to their seats after intermission. I think it might have been better for Schwarz to start over to let everyone get settled; this is a very subtle piece that works best when its air of mystery can be carefully absorbed.

The Symphonia played it rather well considering the aural distraction, with the winds in particular sounding wonderfully sharp, brittle and argumentative in response to somewhat shapeless trumpet playing from the balcony.

The concert closed with a workhorse, the Italian Symphony (No. 4 in A, Op. 90) of Felix Mendelssohn. A staple of chamber orchestra concerts even more than full-size groups, audiences always respond to its wealth of catchy tunes and sun-dappled energy. Schwarz’s tempos were fast and no-nonsense, and he leads his colleagues with large hand and arm gestures rather than always beating time.

This Mendelssohn was generally good, with standout playing from the two horns in the trio of the third movement, and in the opening section of that movement, a gratifyingly quiet dynamic, as Mendelssohn explicitly called for. The closing Saltarello had an exciting forward energy, though it slowed down a bit from the frenetic opening and then cranked up again in the final pages.

The concert opened with the Coriolan Overture (Op. 62), which had plenty of Beethoven’s dark drama following a matter-of-fact opening that would have been more effective if those famous hammer-blows in the opening bars had been substantially more dramatic.