By Robert Croan

Florida Grand Opera’s 2024 version of Puccini’s La Bohème (seen May 2 at the Broward Center) was the 13th production since 1947, which makes it the most frequently performed opera in the company’s history.

According to recent surveys, La Bohème is in the top three most frequently performed operas nationwide, as well, and the work lends itself to varied and varying interpretations. In the old days, it used to be a vehicle for the big-beef singers — vocally and physically — and even today, veteran opera goers recall the likes of soprano Montserrat Caballé and tenor Luciano Pavarotti infusing their prodigious sounds and grand personas into the work’s magnificent star-turn moments.

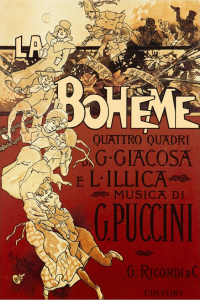

But La Bohème is a story of young people, what we now refer to as “coming of age.” In the closing years of the 19th century, the young Puccini and his librettists — Luigi Illica and Giuseppe Giacosa — fashioned their Italian libretto on an earlier novel, Scenes from Bohemian Life, by the French writer Henri Murger, who was writing about his own experiences as an impoverished writer living with other young artists in a bleak Parisian attic room. Murger’s book is a delightful work, BTW, worth reading on its own merits.

Matt Cooksey, FGO’s director of artistic operations, staged the present production with an eye on the source material, highlighting the four flatmates’ resourcefulness and humor in the face of privation, alongside the bloom of new love and the desolation caused by illness and death. The mostly young cast included three members of the company’s Studio Artist program in principal roles, and while the costumes (by Howard Tsvi Kaplan) and scenery (by David P. Gordon) reflected the opera’s original era, the action played out in a decidedly present-day sensibility. Three full intermissions, however, which is rare these days, stretched one of opera’s tersest scores into a lengthy evening.

Joseph Mechavich’s conducting sparkled with ingratiating instrumental details, keeping up aptly with singers who took abundant liberties with tempo and rubato. Top vocal honors go to the Mimì, luscious-timbred soprano Rebecca Krynski Cox, who brought added dimensions to every phrase she sang. Her entrance exchange with Rodolfo (Italian tenor Davide Giusti) was at the same time touching and insinuating. She carefully contoured the broad lines of “Mi chiamano Mimì” while lending clarity and shading to that aria’s declaratory segments. She commanded the ear throughout, with gorgeous tone and sweeping legato phrasing. And if her death scene was not quite of the five-handkerchief variety, it was simply and eloquently achieved.

Giusti, an adequate but unexceptional partner, was not in her class. His narrow, somewhat nasal tenor penetrated but lacked variety of color. He sang “Che gelida manina” in its original key rather than the often-used half-tone-down transposition, and managed to sustain the climactic high C, though it was not a beautiful sound. He moved well on stage, however, making a credible lover and fitting member of the male quartet, doing his best work in the Act 3 ensembles — appropriately dominating the trio in which Rodolfo describes Mimìs fatal illness, unaware that she is listening.

Craig Verm’s smooth, solid baritone was an asset to his bland Marcello; he contrasted nicely with Giusti in their Act 4 duet. A pleasant surprise was the high-profile Schaunard of studio artist Joseph Canuto Leon. Thanks in part to Cooksey’s canny and keen-eyed staging, Leon made Schaunard’s early-on description of his successful day seem like a mini-aria — even though the other three men were singing in background counterpoint, and this character doesn’t have an extended solo. Filling out the male quartet, Keith Klein, also an FGO studio artist, romped playfully through the lighter scenes, using his dense and resonant bass-baritone tones to touching effect in “Vecchia zimarra,“ the mock funeral march for his overcoat — being pawned to get medicine for the dying Mimì.

Sara Kennedy, still another studio artist, did not project well vocally in Musetta’s midrange tessitura, but she made an attractive, fun-loving figure amid Cooksey’s frenetic staging of the Café Momus scene. Steadfast baritone Neil Nelson, who is also manager of the studio artist program, took on the two comic roles of the landlord Benoit and Musetta’s rich escort Alcindoro with his usual high professionalism, singing rather than barking the buffo outbursts.